Brits Cite Parakeets for War Bravery

Gibraltar (AP)—Six parakeets pressed into service aboard a British destroyer during the Gulf War received citations Monday for bravery.

British Forces spokesman Capt. Leo Callow said the six birds were received with honors at Shell Jetty by children from St. Georges School, who had lent them to the navy to detect chemical gas.

The birds, belonging to the Melopsittacus undulatus group, were recruited to serve on board the HMS Manchester as part of the ship's chemical detection system when it headed toward the Persian Gulf last January.

Actually the pigeons were worth the attention. Quick and reliable, they were indispensable to some of the train-watching circuits and saved courier fives in the process.[90]

Still some agents had to cross borders, and this was tricky business with wartime passport controls. Whereas the French had required passports only of Russians before the war, they now introduced strict, formal conditions for all foreigners wishing to enter French territory. Passports with officially stamped visas became mandatory as of August 1914.[91] Throughout Europe border controls tightened as lax procedures gave way to demands for formal papers in order. The spies countered with false papers fabricated by their intelligence services or procured through other means. Turkish agents traveled to Morocco with Greek and Italian passports. German agents posing as Greeks or Romanians acquired papers from the French representative in Buenos Aires. Neutral papers, clearly, were the most desirable. At Rotterdam the Germans purchased passports from a contact in the town hall for the price of one hundred pounds sterling each, and they replicated the stamp and signature of the Dutch consul in Barcelona to manufacture their own

sham papers from Holland. In China they organized an operation to supply their agents with the necessary documents. Germans and Austrians stranded in the United States at the outbreak of war bought papers from unemployed seamen or drifters to make it back through the British blockade. Sometimes the Germans simply stole papers from neutrals traveling through their country. In Switzerland a Jewish gang sold bogus identity papers to all comers.[92]

As with codes, invisible ink, and carrier pigeons there was nothing new in the fabrication of false papers. Nonetheless, there was a stepping up of intensity whose tone and feel previewed the intrigues of the interwar years. The scale and technical proficiency with which bogus documents were manufactured in the First World War rang of the traffic in the twenties and thirties and had no precedents before 1914. After the war the controls remained, as did the use of counterfeit passports and visas whose demand was forced up by the appearance of large numbers of stateless people and the descent of still more frontier barriers. In the menacing, sinister quality to border crossings between the two wars ran undercurrents of intrigue not unlike those introduced by the wartime passage of clandestine agents.[93]

Thus one facet to espionage in the First World War was the sheer quantitative vault to a new level of action that all but mass-produced spies and tricks of the trade just as the war churned out men and material in every other theater of fighting. Yet another was the conversion of sabotage and subversion into routine forms of intelligence work. Very quickly the secret war turned into a war of covert operations. Demolition teams swung into action in Galicia, blew up bridges in the Balkans, worked their way up rail lines in the Carpathians, infiltrated behind lines in Belgium and France. Factories were dynamited, ships and depots set on fire. Agents traveled with incendiary bombs in the shape of pencils, or with the more sinister weapons of disease. The French warned against German plans to poison their horses, but they were scarcely lily-white. They too experimented with germ warfare or submitted plans to destroy the harvest in Hungary. Andlauer tells of an SR conference where his chief flourished anthrax and glanders tablets, prepared by the Pasteur Institute, before the assembled officers. A promised conference on typhoid never took place, but Andlauer found uses for the first series of germs. "Without boasting of extraordinary results, I can admit to having on my conscience several hundred piglets in the Frankfurt region and also some cattle that left Switzerland for Germany in perfect health but abruptly departed this life once over the border."[94]

Nothing, however, seems to compare with the sabotage organization—the S-Service—that the Germans operated out of Spain.[95] The direction was confided to the three principal agents in the Iberian peninsula—the ambassador Ratibor, the military attaché von Kalle, and the naval attaché von Krohn (replaced by Steffan in 1918)—but eventually the service was run through the cover of a brokerage firm based in Bilbao with branches in the major Spanish cities. The S-Service's schemes bordered on the fantastic, the products of fertile imaginations running feverish and sick. Von Krohn proposed dumping cholera germs into Portuguese rivers to force a border closing with Spain and to undermine Portuguese ties with the Allies. A Professor Kleine from the Cameroons said the plan could be easily executed with two glass tubes and gelatinized cultures (this same Kleine, incidentally, appears in a report from 1921 referring to a wartime project under his direction at the German hospital in Madrid to manufacture typhus bacilli for export to Salonika, Africa, and southern France; whether the report is true cannot be verified).[96] The scheme sounds typical of von Krohn, whose judgment ranged from poor to plain stupid and who compromised himself badly in a personal affair with a French double agent.[97] Berlin nixed the cholera proposal, but it gave the go-ahead for sabotage missions in France and Portugal including the destruction of ships, factories, and livestock. Cultures for contamination initially arrived from Berlin, but soon the S-Service was cultivating its own. An agent from Switzerland delivered explosive materials camouflaged in pencils and thermos bottles, while other materials traveled from Zurich via Italy hidden in toy chalets. Some factories were blown up in Lisbon, but the results in France were paltry compared to preparations and ambitions. Faulty materials thwarted one agent's efforts. Another reported great successes to Ratibor, but these were all fairy tales; the agent worked for French counter-intelligence.

These adventures (and travesties) point to yet another facet of First World War intrigue: the importance of the periphery. The targets, of course, were the warring nations, but for obvious reasons the spies fought their war largely in places like Spain, Holland, Norway, and Switzerland. Spies could not operate with impunity in neutral countries, but they had far more room for maneuver there than behind enemy lines, and the presence of one nation's spies invited the dispatch of another's until intelligence and counterintelligence whorled into an elaborate, incestuous, self-sustaining enterprise. Moreover neutral countries were sources of supply or staging areas for transshipment, and these too

drew spies as sugar draws flies. Much of the intrigue in Holland centered on German efforts to circumvent the blockade by importing blacklisted materials via Dutch middlemen operatives. German intelligence in Scandinavia worked behind fronts such as the International Agency (wholesalers) in Sweden and through agents like the industrialist S. and the merchant A., both based in Copenhagen, and Gertrude L., who worked as a typist for North Sea Packing in Stavanger. German saboteurs planted bombs in Narvik and were suspected of setting fires in factories and warehouses, including one in Trondheim that destroyed a considerable quantity of goods destined for Russia. In Spain, Ratibor and Co. worked the embassies and ministries for tidbits of military intelligence, and von Kalle built an espionage network centered on Bordeaux with agents operating in Paris, Le Havre, Cherbourg, Brest, Marseilles, and Toulon. His principal informer brought all sorts of interesting information fed him by French counterintelligence; he too was a French double agent.

As in Holland and Norway, the secret war in Spain focused on shipping. The Germans wanted information on the quantifies and kinds of supplies coming in and particularly intelligence on shipping routes and patterns that they could send to their submarine commanders. The German admiralty instructed von Krohn to gather information on maritime traffic and cargoes throughout the Atlantic, and von Krohn responded by establishing a network of informers from Barcelona to Cádiz to Bilbao who reported ship cargoes and itineraries, convoy assembly points, and other data necessary for submarine warfare. In turn the French and British filtered agents into Spain to fight against the spies and to watch the submarines.[98]

The greatest of spy playgrounds was Switzerland. In the 1940s the Swiss liked to refer to themselves as a lifeboat. For the First World War the appropriate analogy would have been a luxury liner on a secret agent cruise. One can imagine how easily the simile could be extended: the public room encounters; nods in the corridors; exchanges at dinner or in the casino; intrigues—petty and grand—in the staterooms; a constant, underhanded flow of news, gossip, innuendo, and assignation; dirty work down below; a crew that steered, serviced, and supervised but intervened only in moments of exception. Such was Switzerland between 1914 and 1918. Shift the analogy slightly to one vast resort—suspects in reports are nearly always identified with the hotel they are staying in—and the picture is practically complete. The Italians called Lugano "Spyopolis," a city of Swiss, Slav, German, Russian, Italian,

Spanish, Dutch, Brazilian, and French spies. Ladoux of French counter-espionage, in one of his few credible passages, told a man he was sending into Switzerland:

There is where people the Allies consider undesirable, outlaw, [or] suspect take refuge. Some have always been traffickers. Others are only spectators at first. Or they are fine fellows with nothing to do. Now, the cost of living is high over there. Room costs are always going up. After several weeks refugees bereft of means are forced to earn money. The spy trade is there, it's tempting, just about the only job they can get except for another obvious one. Moreover the two trades go together. Charming and spying, that's what three out of ten—let's be modest—suspicious neutrals turn to.[99]

The assessment was not far off the mark. Mata Hari was the most celebrated of these kinds of spies (despite the fact that she did almost nothing in the war). But there were plenty of other femmes galantes whom French intelligence identified as suspects or prospects and who traveled or worked at some point in Switzerland. A sampling from one file produces Marguerite S., German-born, a singer calling herself Radhjah, a sometime French agent when she worked the Corso Theatre in Zurich; Marie M., who traveled to Switzerland to see her Austrian lover; Frida M., born in Hamburg but a French national, a dancer in several Geneva establishments, "signaled as a spy"; and Juliette T., a Swiss national, an artiste , who made suspicious trips across the border into France.[100]

A neutral country bordering on four belligerent states, a haven for exiles and draft dodgers, a spa for the rich and a retreat for the invalided, an exchange point for prisoners of war, a land of business and transshipment, a tryst for international lovers, Switzerland offered an unparalleled setting for wartime intrigue. The country was a contact point for information, a nexus from which spies were dispatched and to which spies returned with reports. It was a locale where nationals from belligerent states had legitimate reasons for congregating, thus making it a round-the-clock rumor mill and an ideal milieu for picking up stray pieces of intelligence. Spies all but tripped over one another in train compartments, in lobbies, or at dinner engagements. The scene has probably been fixed for all time in Somerset Maugham's Ashenden stories about a British spy in Switzerland during the war (Maugham himself worked in Switzerland for British intelligence):

While he waited for his dinner to be served, Ashenden cast his eyes over the company. Most of the persons gathered were old friends by sight. At that time

Geneva was a hot-bed of intrigue and its home was the hotel at which Ashenden was staying. There were Frenchmen there, Italians and Russians, Turks, Rumanians, Greeks, and Egyptians. Some had fled their country, some doubtless represented it. There was a Bulgarian, an agent of Ashenden, whom for greater safety he had never even spoken to in Geneva; he was dining that night with two fellow-countrymen and in a day or so, if he was not killed in the interval, might have a very interesting communication to make. Then there was a little German prostitute, with china-blue eyes and a doll-like face, who made frequent journeys along the lake and up to Berne, and in the exercise of her profession got little tidbits of information over which doubtless they pondered with deliberation in Berlin. She was of course of a different class from the baroness and hunted much easier game. But Ashenden was surprised to catch sight of Count von Holzminden and wondered what on earth he was doing there. This was the German agent in Vevey and he came over to Geneva only on occasion.[101]

The archives bear out the ambiance of the literature. French intelligence in Switzerland turned up people like the Greek Athanassiades who had run guns for the Turks in the Italo-Turk war and then an espionage service between Greece and Egypt for the German military attaché in Athens. Now he was in Geneva where he associated with a shady assortment of individuals. He was not, the SR noted, to be confused with another Athanassiades who resided in Lausanne and was equally suspected of espionage. The French also stumbled onto a German spy in Zurich named Willer and his associate, another German agent named Brigfeld, who had been born in Patras but was now living in Zurich where he was mixed up in Greek affairs. There was Alexandroff, a questionable Bulgarian, and a Colonel Bratsaloff, whose espionage organization sounds suspiciously like a private operation. Another report identified forty-two Turkish agents stationed in Switzerland in 1918.[102]

At a more prosaic level French agents tracked the movement of goods, watching for contraband imports to Germany via Switzerland.[103] Away from the hotels agents like Lacaze ran low-level yet dangerous operations that seeded informers throughout Switzerland and on into Germany. Relying largely on Alsatians like himself, Lacaze was able to set up a listening post in a modest hotel in Basel. Another operative, code-named Hubert, traveled to Germany on business trips. On his journeys Hubert jotted down a meticulous record of his affairs and expenses. Orders totaling 580 marks from Schmidt and Co., or room costs and tips at the Hotel Metropole in Stuttgart, were just that. But numbers regarding stamps, cards, and beer referred to troop units and their movement by train. Lacaze never gave his name or his address to his agents. He told them the time of day and the place for their next meet-

ing and that he would send them a postcard reading simply, "Best wishes, Louise," whose date would be the day of the rendezvous. The agent was to arrive no sooner than five minutes before and no later than five minutes after the prescribed time. If the agent needed to see him in the interim, the agent was to take out an advertisement in a Swiss newspaper, for example, listing a kitchen stove for sale. Either Lacaze would come the next day or he would send his postcard with the date.[104]

As in Spain, the espionage war in Switzerland turned toward a war of covert operations. It was from Switzerland that explosives made their way to the peninsula and it was through Switzerland that Andlauer's agents struck at livestock for Germany. In the last year of the war authorities discovered a cache of munitions, grenades, and propaganda that had been brought in from Germany and transferred via the German consulate in Zurich to an Italian deserter. The conclusion of French counterespionage was that the German general staff was planning terrorist attacks in France and Italy through a secret terrorist operation it was organizing in Switzerland.[105] In the wake of German sabotage adventures in Spain and elsewhere, this was not that farfetched a perception.

In the end almost all the secret war on the periphery turned into a war of sabotage and subversion because that, ultimately, was what all peripheral strategy in the First World War was about: striking where the enemy was weakest, diverting his attention and forces, undermining his cohesion, and undercutting his sources of supply. As the conflict escalated into a global war expeditionary forces sailed to faraway places like Iraq, Egypt, and the Dardanelles, and fought sideshows in East Asia and eastern and southern Africa. However the weapons of choice in global strategy remained sabotage and subversion because these dangled before the eyes of the war makers the hope that a very few hands might yet pluck great ripe fruits from the tree of victory.

All sides fought a covert global war. The Allies produced the most celebrated subversive—T. E. Lawrence—so celebrated that other adventurer-spies would be reduced to the generic Lawrence epithet: the German Lawrence, the Japanese Lawrence.[106] Yet the easiest territory for the Allies to exploit was central and southern Europe, whereas they themselves, as the holders of empire, were most vulnerable to the subversive intrigues of their enemies. It was the Germans who had the greatest field of play and the wildest visions to match, although in the end they had precious little to show for their efforts.

In the Americas, German agents, often fighting competing covert

wars with one another, occasionally operating on orders from Berlin (via the intermediary of Madrid station), more often than not marauders on the loose and running amok, hatched an unending series of grandiose schemes. They were going to sabotage American munitions factories and harbor facilities. They would place explosives on ships carrying supplies to Europe. Strikes would be fomented, the Panama Canal Zone would be sabotaged, the Tampico oil wells would be destroyed. They intrigued with Mexican generals to strike north against the Yankees and thus embroil the United States in a Mexican war, or they schemed to overthrow Venustiano Carranza and to replace him with generals or a dictator more compliant with the war needs of Germany. The Zimmermann telegram was merely one variation on a steady stream of German proposals to make use of Mexico in the global strategy of war. Still further south they planned to sabotage mining operations in Chile or to destroy livestock destined for Europe.

Some of these projects were actually executed. In 1916 German agents set fire to the Black Tom shipyard in New York and a factory in New Jersey. Another German agent named Jahnke, who had been a private detective and presumably an arms and drug trafficker in San Francisco before the war and who was one of the few German spies with the wits and skills to match his imagination, claimed to have destroyed several ships and a factory in Tacoma, Washington. Other agents smuggled bacteriological gelatins to a man named Arnold working in Latin America as a spy, propagandist, saboteur, and, apparently, specialist in germ warfare. In early 1918 Arnold reported that mule shipments to Mesopotamia had been "copiously worked," and that his sabotage of Argentine horse shipments to France had met with success. But these were mere drops in the bucket compared with what had been anticipated. Most projects never got off the ground either because the authorities in Berlin refused to send money or scrapped schemes as unfeasible or because most of the German agents were an incredible collection of blockheads who played right into the hands of their enemies. The Allies too, especially the Americans, ran their own covert war in Mexico. Practically all German agents were constantly under surveillance, and there is reason to believe that the British sabotaged a German radio station in Ixtapalapa, although the source, as usual, was anything but credible. Everyone, including Carranza, seems to have been running a network of agents.[107]

Elsewhere the Germans sought to raise North Africa against the French and British, Persia against the British and Russians, India against

the British, and Indochina against the French. They and their Turkish allies promulgated a jihad, or Muslim holy war, as money, arms, and agents poured into Morocco. In Libya Turkish and German agents goaded the Senoussi to strike at Egypt's western border. A Turkish expeditionary force marched toward Suez, preceded by Turkish secret service guerrillas and supported by Turkish agents in Cairo, while German agents planned the sabotage of the canal and the raising of Egypt. On Christmas day 1914 the German explorer Leo Frobenius left Damascus for Abyssinia to fan an insurrection in the Sudan. Indian revolutionaries were wooed, promised support. As far away as Madrid von Kalle contemplated the dispatch of agitators to India. Two expeditions, under von Hentig and Niedermayer, set off across Persia to incite the Afghans to rush upon India's northwestern frontier. Another German agent, Wassmus, headed toward southern Persia to organize tribal harassment of the British. Still other agents, including members of the Afghanistan expeditions, prodded Persia toward war against the British and Russians, offering money, munitions, and officers as support for the enterprise. A sabotage team temporarily cut the oil pipeline in Persia and stood ready to seize or destroy the installation at Abadan. Meanwhile agents in Latin America dreamed of covert operations in China and provoking Japan against Britain, some indication of the way the war gulled imaginations into fantasizing strategies of worldwide subversion. More materially German intrigues and money came together with nationalist movements to stir up troubles in French Indochina.

As in the Americas, none of these projects amounted to much. There was to these vast enterprises a whimsical and improvised character that too often outstripped German resources. In the end the Germans had little more to offer than resourceful agents and vague promises of money, arms, and postwar restraint. Personal rivalries and shoddy planning supplanted method and organization. Quarrels rent the Afghanistan expeditions while authorities forwarded Niedermayer's baggage through the Balkans with the label Traveling Circus attached to the cases. They might as well have plastered the boxes with red stickers reading Espionage. The consignment was confiscated in Romania after a customs official opened a case and found a machine gun and bullet packets within. Bribes lubricated the passage of a second baggage shipment. The men on the spot like von Hentig and Niedermayer were capable of extraordinary exploits (and on the level of maneuver, if not that of grand politics, they consistently outwitted their adversaries and then their pursuers).[108] At the very least, however, the subversion of empires required

a stronger military presence than either a handful of Germans or their Turkish ally could muster and greater coordination between German and Turkish policy in Asia. French, British, and Russian countermeasures were vigorous, a lesson not lost on the shah of Persia and the emir of Afghanistan who might have had little liking for the English but who understood power and the consequences that come with lost causes. In Indochina the nationalist movement was too weak and divided to be more than an annoyance. Ultimately German global intrigues mattered more for what they signified than for what they accomplished. They were ambitious, even at times ingenious; but they produced practically nothing in the way of concrete results.[109]

This could be the epitaph for all the spies who perished in the First World War. The secret war was fought in great numbers, all over the world, yet it cannot be said to have altered in any way the outcome of the conflict. No doubt the mountains of tactical intelligence—troop and ship movements, orders of battle—helped prevent blunders and save lives. But all sides compiled this kind of intelligence and plenty of lives were wasted nonetheless. It is difficult to see how the basic facts of the war—Allied victory in the west, Russian defeat in the east, a war of stalemate and attrition—were in any way the result of intrigue and espionage or could in any way have been changed by them. Even bold strokes like the interception of the Zimmermann telegram did not have the strategic consequences some have attributed to them. There were no secrets whose discovery would divert the course of the war, and raw intelligence itself was only as good as the staff's evaluation of it and then the decisions the generals made as to whether to use it. There was something insular, almost bubblelike about much of the spy war: spies pitted against other spies, tracking and neutralizing one another. It was a fascinating, dangerous game played by all sides, but one wonders whether the risks were any more vindicable than those for the men who went over the top or whether the successes meant any more than a trench captured here or a freighter sunk there. One is reminded of Paul Allard's 1936 debunking of Basil Thomson, the fabled head of British counterespionage in the First World War, who, summoned by Paris-Soir to solve the sensational Prince murder in the mid-1930s, "collapsed in his seat at a famous Dijon restaurant following libations and gastronomic excesses that seem to have been the principal concern of 'the man of a hundred faces.'"[110] A bit cruel and certainly unfair, but also an exposé of the inflation of spy reputations and the role of the spy from a man who made a living passing on every espionage story he heard.

Intrigue, then, did not shape the First World War, but the war did shape intrigue and in this relation the historian can find something significant. More than the bloated accomplishments of spies it was espionage's ability to capture styles and moods that came with the war and to replicate in its symbolic presence the changes introduced by that cataclysm that make it worthy of our attention. Those characteristics of interwar espionage that would bind it to its times—its copiousness, its scale and subversive orientation, its global reach, its methodical proficiency, and its more diverse or sophisticated motifs and imagery—emanated from the far-reaching consequences of the Great War, but also from the war experience itself and the way war made real what previously had been only imagined or conjured. Postwar espionage never lost what it acquired with the dramatic expansion of intelligence opera-dons during the conflict, nor did the French forget the lessons the war taught them about the vital importance of rear lines and imperial security that would feed postwar obsessions with spies. Invariably as this study progresses it will retrace its steps to that conflagration, whether in discussing spy fears of the late 1930s and memories of wartime subversion and sabotage, or in reviewing the interwar spy literature that grew out of the war, or in recounting the ties between espionage and adventure on the one hand and the wartime exploits of a von Hentig on the other. War in 1870 began one era in espionage; but a wider, deeper, far more bountiful one surfaced with the spy wars fought out from 1914 to 1918.

Perhaps it is Impex that tells us best how sharp the break was between one era and another. We are talking about a German import-export firm (hence its name Impex), in reality an intelligence front, based in Barcelona but with branches that the French unearthed in other Spanish cities in the early twenties, or so they believed. The firm traded in a variety of goods—machines, mining equipment, automobiles, dyes, pharmaceuticals—imported from Germany and then reexported to Spanish Morocco. But mostly its exports were guns and munitions and French agents backed these charges up with a litany of others against the house. Impex claimed to be a branch of a central business in Madrid, but there was no foundation to this declaration. Impex's trade was lively, but rarely was it conducted under the firm's own name. A Spanish freight-forwarding company that had collaborated with German espionage in the war and reputedly held to those arrangements shared a ground floor

Map 1.

Spain and the Moroccos.

and interior staircase with Impex, covering the latter's "shady and suspect" traffic to Morocco. Running Impex's warehousing was a waterfront tough, Luciano A., who had spied on Allied shipping during the war for the Germans and had attempted to plant time bombs on boats. Across the Mediterranean at Melilla and Ceuta Impex had connections with the B. brothers, importers and exporters suspected of shipping arms to Arabs in both Spanish and French Morocco. The director of Impex was a man who had worked for the Mannesmann brothers (a name we will return to) before the war, and his two associates were German agents. All three took their orders from Pablo S., the German intelligence agent in charge of operations in Morocco or from the Rüggeberg brothers, who ran German intelligence in Spain after the war (and reports from French files suggest the continued presence of a sizable German operation in the Iberian peninsula).

Tales about Impex passed onto the French were charged with mystifications and dense atmospherics. The house was frequented "by every-

one Barcelona numbers among former and current German agents or Spaniards notoriously Germanophile. Impex receives numerous cases that it mysteriously dispatches to southern ports; it sends agents to Melilla who meet there with Moroccan dissidents." There were communiqués on Max W., who appears to have been running Impex by December 1922, describing his voyages to Spanish and French Morocco ("without papers , he claims") in the course of which he held long conversations with a Jewish banker and shipper. In August 1922 a secret bulletin to the Ministry of Colonies related the arrival of Karl G. and Friedrich L. from Madrid and Málaga, Impex agents recalled to headquarters for days of close quartering with the bosses before setting out for Andalusia, and who blabbed at the Gambrinus Bar prior to departure that they were on an urgent mission to Ceuta, Melilla, Tetouan, and Tangier. Such reports were heaviest from the fall of 1921 through the course of the following year. Then the reports faded, although Impex died a slow death in French consciousness. Late 1925 produced still more references to Impex, this time recounting the questionable conduct of Walter R., a former German policeman who had lived for some time in Barcelona, traveled frequently to Morocco, had his mail addressed to a Dutch company care of a post-office box in Santander, and whose principal occupation seemed to be recruiting secret agents for Germany. R. was closely associated with Impex, as well as with a man suspected of infiltrating narcotics into France. Several years later the Battiti affair once again (appropriately) resurrected mention of Impex.[111]

For Morocco, where international intrigue was endemic from the end of the century, all but writ into the resonance of the place-name, Impex was a likely phenomenon. Before the war the pattern of resentment, defiance, and outright revolt upon which the French had built their command of the country[112] had set the stage for foreign intrigues against the conquering nation. Pan-Islamic conspiracies, aimed at fomenting tribal risings and launched out of Cairo, had created moments of discomfort before they sputtered out rather ingloriously, the few men who made it to Morocco falling easily into French clutches.[113] Germans had run guns on the freighters of the Atlas, OPDR, and possibly Woermann lines, all three shipping companies out of Hamburg, the latter two operating a scheduled service to Morocco or the west coast of Africa by the turn of the century. Heinrich Ficke, the German vice-consul, had watched benignly as the Atlas's Zeus unloaded its contraband cargoes at Tangier and Casablanca, although he was also the com-

pany's local representative, and rogue diplomacy and commercial imperatives (both the Arias and OPDR lines were running more ships than their routes warranted; Arias went into liquidation shortly after its founding) more than official scheming may well have explained this trafficking in arms.[114]

There were also the Mannesmanns, six brothers in all, who owned a successful seamless pipe company in Germany and who had come to Morocco in pursuit of mining concessions. Mavericks and adventurers, they were German robber barons whose enterprise radiated great force and energy, but they could also be malevolently serf-destructive and inclined to plot when they could not get their way. Thwarted at obtaining French government approval for the extensive mining concessions they had won from Moroccans, the Mannesmanns turned to intrigues. They incited separatist movements in the south of the country and worked with gunrunners. They maintained an arms depot on one of their farms, and their geological expeditions into the Arias distributed guns and anti-French propaganda. During the Agadir crisis in 1911 Mannesmann agents sought, unsuccessfully, to create an incident that would force a German troop landing. Their wide connections with the German community in Morocco, their contingent of engineers, mining assessors, and protected nationals who traveled all over the country, and their success in wrapping themselves in the cloak of German national interests to the point that pan-Germans looked upon the Mannesmanns as the principal tacticians of an imperial strategy, appalled the French, who had every reason to regard the brothers as German secret agents, although it is not certain that German authorities who negotiated Mannesmann claims did not grow to despise the brothers as much as the occupiers did. Nonetheless Mannesmann was a name the French would not forget easily, as report after report from the war, and the Impex file, attest.[115]

But the background to Impex was really the First World War and Germany's effort to raise the tribes against the protectorate. There, overseas, amidst the casbahs and the desert, no less than on the trailways of Europe, the war propelled the French into a word of spies they scarcely knew before the firing began. Wartime in Morocco cultivated the same assortment of ninety-day spooks and inflated support networks, the same grandiose projects and spy-counterspy battles that it produced on the continent. Under the banner of a jihad German agents, money, arms, and propaganda flowed toward the country.[116] First came a German officer named Lang, traveling with an American passport and probably calling himself Francisco Farr, although a number of reports includ-

ing one as late as 1918 refer to him as Francisco Fart.[117] Then when Lang took ill and died in 1915, German contact with Abd-el-Malek in the north continued through Albert Bartels, a former tradesman who had come to Morocco in 1903, had learned to speak Arabic, had been interned in 1914 but had escaped, and who had, at least for some time before 1914, worked for the Mannesmanns—exactly the sort of connection that the French were apt to seize upon.[118] Later the Germans sent out a Dr. Kuhnel, who took on the identity of José Maury from Colombia and who carried a credit for a considerable sum of money to organize more rebel resistance.[119]

To finance and arm a full-scale war of Moroccan resistance (even if this never came about) required the creation of a considerable infrastructure of support and supply and this the Germans established only after 1914. They operated agent networks in the towns of Spanish Morocco—Ceuta, Tetouan, Melilla—and transit bases on the Canaries. In neutral Spain German intelligence easily recruited agents among the thousands of German nationals who had arrived since the beginning of the war from West Africa, Morocco, Latin America, and Portugal. Ratibor, yon Kalle, and von Krohn in Madrid provided central direction for Moroccan affairs, although operations spread throughout the country. In Barcelona the Germans established their propaganda center. Contraband arms shipments passed through Seville and Cádiz. Melilla's staging base was in Málaga. There at a small brasserie in the calle Marques de Larrios the gathering often included a Mannesmann brother, the engineer Langenheim, whose name would reappear in French intelligence reports in the twenties and thirties, and a man named Stalwinger.[120]

None of this made any difference at all, despite the fact that Lyautey's wartime correspondence paints a picture of unrelieved alarm about the danger of pan-Islamic propaganda and "Germano-Islamic" intrigues.[121] Germans and Moroccans could agree on common enemies but on little else. Coordination between rival Moroccan factions was tenuous at best, while relations between Abd-el-Malek and his German liaison, Albert Bartels, were horrid, bordering on the mutually contemptuous and recriminatory. Realizing that their anti-imperialist clothing was full of holes, the Germans sought Turkish cover, but that garb proved tawdry and frayed. Turkish agents dispatched to Madrid in late 1915 squabbled with their ally, demanded more money, and threatened to tell all to the French if the Germans did not pay their way to America. Spanish police arrested another Turkish agent, posing as Manuel Rodriguez from Peru, for sexually abusing a little boy.[122] As for Stalwinger of Málaga, he was

little more than a brute, an ex-legionnaire who went under the names Pfeffer, petit doseur, and Fulenkampf, notable mostly as a type of gorilla that would overcrowd the spy worlds in the interwar years. The Germans kept him around because he would do anything. His contribution to the war was probably less than nil: money sent from Madrid was wasted on his private debaucheries, and a mission to Algeria ran aground when in an alcoholic stupor he announced that he was planning to encourage desertions among French legionnaires. By mid-1915 he was confiding in a man who was a French counterespionage agent.[123] Then there was the captured informant Georg Regenratz. Under interrogation he refused on his honor as a German officer to confide a German code, at other times offered if set free to go to Berlin and bring back important documents, spoke of his needy mother and his personal finances, which were a mess, and, in the end, spilled the beans about circuits for infiltrating agents into North Africa.[124] Even without these clowns the French had little to fear. They countered the German offensive with vigorous counterintelligence measures and their own contingents of tribesmen, retained a monopoly of firepower and control of the sea, and introduced smart policies regarding the indigenous population, such as the creation of jobs. These, more than German failures, held Morocco for France.[125]

Yet the Bartels, the Langenheims, the von Krohns, and the Rcgenratzes, as well as the Mannesmanns, when taken together, represent the distance intrigue had traveled since 1914. Their enterprises produced no results but stirred up plenty of noise and a thorough air of mystery, and that was the kind of clandestine war the Germans brought to Morocco: submarines that surfaced in the night with money and armaments; false passport ateliers in Italian port cities; thugs gone to seed with too much drink and amateur adventurers who took on names like Si Hermann (Bartels) and blew up railway bridges in the back country; a mysterious German woman who appeared in Melilla, called herself English, proclaimed her engagement to a typewriter salesman out of the Transvaal, and promenaded at night with a Spanish captain of police.[126] The postwar years would offer no better, but also no worse.

The memories were themselves a legacy, because what the war left behind was the almost unerring tendency to reproduce the details and imagery of First World War espionage. Nearly every report carried with it something from the wartime experience, although not always in the same way. Occasionally it was conditioning, the inclination to think about subversion following a war of insurrection or the far-flung dimen-

sion to interwar reporting after a war that had witnessed German arms shipments to Morocco, sabotage plans at Suez, and expeditions to Afghanistan. At other times it was a sense that the intrigues of wartime were continuing, as in the reports of German/pan-Islamic combines, now with Comintern imagery cooked in, that piled up in the years immediately following the armistice and repeated the basic facts—conspiracy, systematic coordination, global connections—of the First World War in Morocco. Or there was simply the discovery of spy rings and operations strikingly similar to those of the war.[127]

And that is where Impex fits in, because in this shadowy company we can see how nearly all these strands could come together. As a covert operation Impex emerged from the war and the events that had followed. For some of its operatives like Luciano A., the war with its gluttony for agents had been the initiating experience. For others, like the Communist agitator Fernando V., who hung out at the edges of Impex reports, it was postwar milieus that created openings and reasons for action. Still others stepped out of the war, like freight-forwarding accomplices or Friedrich Rüggeberg who had worked for German intelligence in Spain during the fighting.[128] In the references to Mannesmanns as directors behind the scenes there remained the nagging inclination to identify a chameleonlike consistency to German intrigues carried over from earlier times. Yet mostly there was to Impex a subversive, far-reaching quality—reports on the firm extended its operations to the Cameroons or converged with warnings of insurrections throughout the Muslim world—that carried with it the aroma of intrigue since 1914.

Above all else Impex projected the fullness that came with the war. It recalled the German wartime organization assembled in Spain to run arms and money and agents to Morocco, although not any organization that had preceded those years. In that respect even the question of veracity placed Impex squarely within the postwar scene. Whether Impex, as the files reconstruct it for us, was fiction or reality is not at all certain. The reporting was extensive and the details specific. Everything tempts us to believe that the operation, in some form, existed. But if Impex was a fabrication it was of postwar construction, a vision of German espionage in Spain and Morocco concocted out of the wartime experience and the focus of intrigue in the après-guerre world: subversion, communism, colonial security, and global surveillance. In its details and its internal coherence, Impex could be imagined only after the war. Such was the case of nearly all interwar intrigues in Morocco. Whether fact or

fiction, their building materials were those of the war and of the conditions that followed.

Thus over the years the differences with the past grew more pronounced. By the 1930s espionage in Morocco reflected the organizational and global designs characteristic of the interwar age. Gone were the reports of rogue settler intrigues or the fastidious details on individual arms shipments. In their stead materialized broad schemes of infiltration and espionage launched from European centers with method and operational sophistication and matched by extensive and systematic accounts on the French end.[129] Seditious techniques now included movies, records,[130] or the beaming of subversive radio messages across vast expanses of the world—the radio wars, as they came to be called toward the end of the decade.[131] Characters and networks were those that only the postwar period would know. As before, Germans predominated, but the heady brews of the thirties encompassed all the bogeys: Italian Fascists (who initiated the radio wars and whose infiltration of the Moroccan Italian community was carefully watched), Spanish Nationalists once the civil war began, and in other extensive communiqués, agents of the Comintern.[132]

Spanning nearly all of these was the overarching presence of Shakib Arslan. William Cleveland, in his authoritative biography of this influential yet relatively powerless pan-Islamist, has exposed the mythic dimensions to French and British images of the man as the ultimate string puller in the Arab Middle East. In reality Arslan led a ragged, if heated, existence. He was a mentor and a spokesman, but rarely a conspirator. The mysterious powers bestowed upon him by imperial officials were, however, symptomatic of an era in which nationalist agitation coincided with systematic subversive activity from abroad. Arslan spurred on the myth with his close ties to Germany and his apologies for Mussolini. Essentially he would turn to anyone who he thought would support the Arab cause, and if French documents are to be believed—and on Arslan they are suspect—he was also in league with the Communists. In this he too, like Impex, was a product of his times. He had been won over by the kaiser's proclamation of support for the Arabs at the end of the century, but the truly formative years for the man were those of the German-Ottoman alliance in the First World War and the active pursuit of Islamic independence. Forever after he was a creature of his own personal memories and missions in that war. But then so, too, were the French who never forgot the pan-Islamic experience of 1914-1918, nor the intrigues that followed, and who, caught in crosscurrents of the

age, turned him into the formidable force that he almost certainly would have liked to be.[133]

All of which recalls the problems with which this chapter began: exactly what changed with the war? In a sense espionage has always been about war. In the twenties and thirties it was about many wars: the Rif war in the northern mountains of Morocco, the Spanish civil war, the erupting war in the Pacific, the war people expected to come. But above all it was about the war that had been fought between 1914 and 1918. Out of this war came the people and the imagery that made up the espionage worlds of the interwar years. Bolshevism, fascism, and future-war literature channeled interwar espionage down avenues of subversion and sabotage or of covert networks of global dimensions. Yet it was the First World War that turned these into the conventions of espionage just as, in effect, the new ideological systems and next-war speculation were themselves products of that war. After the war, espionage in its themes and motifs was always, in some way, a reflection back on the years of fighting and the world that had followed, whether through secret-war imagery or secret-agent memoirs or the constructs and visions of how espionage was conducted.

In this it drew on the network of materials that had developed from espionage and war in the late nineteenth century. At times the parallels could be striking, particularly when the imagery gravitated toward spy mania or when espionage was incorporated into the literature of military defeat. The Franco-Prussian War set people thinking about spies and protracted the consciousness of espionage deep into peacetime. It led to the creation or expansion of intelligence services on a permanent footing and to intrigues not always dissimilar from those that preoccupied authorities in the interwar years. The institutionalization of espionage operations made possible the spy battles of the First World War, and in certain ways anticipated those battles just as prewar espionage themes often previewed those of the postwar.

But rarely were the themes exactly the same. There was, for example, no equivalent to secret-war imagery before 1914. After 1870 French thinking on espionage often turned back to the Franco-Prussian War, but it did so as a disquisition on defeat, German danger, and German iniquity, or as an argument for constructing an intelligence service before the next conflict. Secret-war imagery after 1918 was different. It issued from sentiments made possible by four years of a war that seemed as if it never would end and by the sense of fluidity and unsettlement

unleashed by this war that carried clear through the armistice and the treaties. Secret-war imagery was about extension and permanence. It was an expression of unending war, a description, more than a warning, of a war continuing on clandestine fronts where spy masters were the generals and secret agents the combatants. "'Making war in peacetime,'" wrote Colonel Nicolai in his memoirs in the twenties, "that is the best definition of the present role of the secret service."[134]

Comparable distinctions could be found in fifth-column imagery. There was something timeless, universal to fifth-column projections. No age nor place could call them all their own. The late nineteenth century spawned a genre of literature and reporting about the covert threat from within. Spy panics erupted everywhere with the outbreak of war in 1914. Attached to fifth-column imagery in the thirties and forties was a tradition trailing back into time. Yet fifth-column thinking in these years was also different from any that had preceded it, possessing identifications peculiar to its age. Partly this was a matter of perceptions. When people wrote or spoke of the fifth column they had in mind a specific conspiracy without antecedents. Fifth column described a fascist mode of operations first witnessed in the Spanish civil war and then deployed on a grander scale by the Nazis. It connoted modern espionage techniques—propaganda, sabotage, subversion, and terror—practiced by twentieth-century political systems. For contemporaries fifth column was a custom-fitted concept. The very perception of newness, the conferring of a name—fifth column—made it novel, separate, distinct from the past.

Likewise the fifth-column image that crystallized in spring 1940 was a sum greater than its parts, but one whose equations were sturdy and whose calculations faltered only at the end. The power of the First World War to make real what in the past had been primarily imaginary contributed to the subsequent inflation of the role of the spy despite the failure of espionage to alter in any way the course of that conflict. The experience of total war underscored the cardinal importance and hence the vulnerability of centers behind the front lines as well as imperial resources spread across the globe, all of which had been subject to infiltration or attack by espionage networks during the war. Sabotage, subversion, revolutionary tactics, the sheer number of spies and then the number of their memoirs all projected into the interwar years the perception of the secret agent as a potent force in shaping world events. Later, internationals of all stripes and colors, the ideological clashes of

the thirties, secret-police tactics carried abroad, colonial shakiness, and future-war imagery gave to fifth-column thinking a specificity and coherence unknown in earlier spy panics.

Moreover, if fifth-column imagery was prone to extraordinary flights of fantasy, its essentials never strayed very far from realities. Refugee politics, with their plague of double agents and their tactics of terror and infiltration, familiarized a generation of French citizens to an espionage style that surfaced elsewhere in the form of Comintern subversion or fascist penetration of national populations abroad. The greater scale of networks after the war, their greater system and method, carried fifth-column overtones, as did the new technological opportunities for behind-the-lines infiltration like the radio wars fought over North African airwaves. Out of the thirties came the fabulous tales of the purge trials and the very real terrorist attacks by the Cagoule or, as we shall see, by fascist agents in France. The very nature of the Spanish conflict—ubiquitous, terrorizing—bestowed credibility on the concept that was born with that struggle. Thus in 1940 authorities and populations could envision as real or reasonable the intrigues ascribed to the German fifth column, because fifth-column imagery evolved out of espionage milieus they had known since the Great War. Indeed after the senseless orgy of spy panic in the first days of August 1914, one might have expected greater skepticism in the future, much as Europeans discounted reports of the Holocaust because they had heard similar stories in the previous conflagration. Only the experience of intrigue in the course of that conflict, and then throughout the twenties and thirties, can explain the persistence of these hysterics as another world war began.

Just as the First World War altered the character of espionage, intrigue in the decades that followed reflected historical change more than it did historical continuity. The remainder of this book will examine those changes and the shared relations of espionage and history between the two wars. Subsequent chapters will explore spy literature and the global dimensions to espionage after 1918. They will show how spy tales reflected a particular kind of interwar writing, how themes and style were those of the twenties and thirties, and how there was a complexity of vision to this literature, one where a danger was present but not necessarily overwhelming. They will also show how the far-flung reach of interwar intrigue borrowed from the war, from adventure and travel and a need for romance, from the present-mindedness of these years, and from the realization of an altered relation between the periphery and the center. First, however, one must turn to milieu, and to the richness and representativeness of intrigue in the entre-deux-guerres .

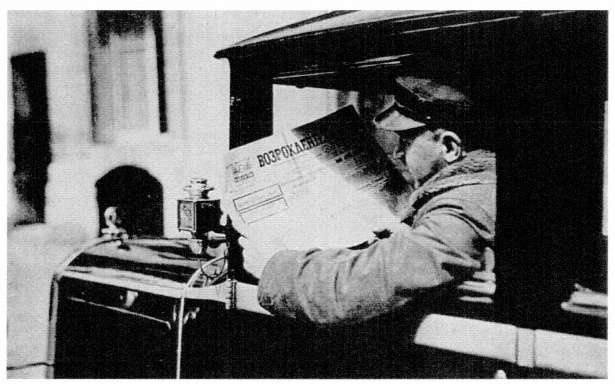

Figure 2.

Taxi of the Don. From W. Chapin Huntington, The Homesick Million.