Nine—

On Knowing Other People's Lives, Inquisitorially and Artistically

Joseph H. Silverman

The epigraph for my essay comes from the play by Lope de Vega, El niño inocente de La Guardia . Its words—spoken by a Jew—are a dramatic summation of many significant aspects of this conference:

What King and Queen are these [Ferdinand and

Isabella] who

through such chimeric schemes

—based on secret counsel—

would send into exile those

who scarcely offend them?

What flames are these, rekindled

from ash by Dominican hordes?

What new Cross is this, black and white,

that delights the Catholics so?

What new mode of scrutiny and

legal system have we here?

Why are trials now held in secret?

Oh, if only Spain had never known such rulers!

Woe unto us, exiled from our own

fatherland in such misery!

The suffering that so long ago was foretold

has not yet ceased and our

punishment is unending.

(Pp. 59–60)

In an unforgettable moment of epiphanic self-revelation, the squire in the anonymous sixteenth-century novel Lazarillo de Tormes confesses to his young servant that, if he had a chance to serve a noble master, he

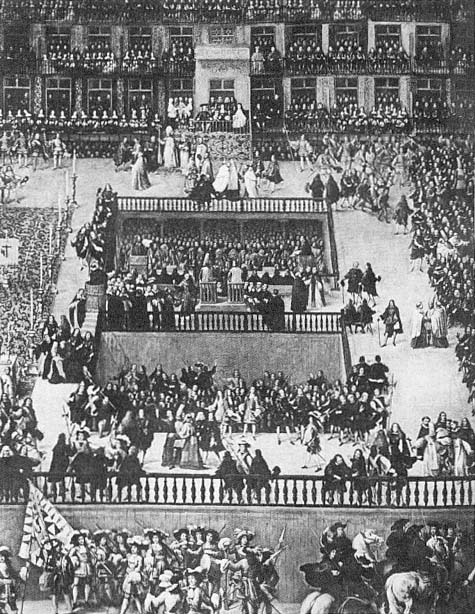

Fig. 6.

Auto de fe by Pedro Berruguete.

would—among other virtuous (!) acts—"be malicious, mocking, and a trouble-maker, a malsín , among those of the house and outsiders; [he'd] go prying and trying to know other people's lives so [he] could tell his master about them. And [he'd] do all kinds of other things of this sort which are the vogue in palaces today and please the nobility well" (p. 57). As Covarrubias informs us in his Tesoro de la lengua , the malsín, a word of Hebraic derivation, is "that individual who secretly warns the authorities of the transgressions of others with evil intention and self-interest, and to perform this function is called malsinar" (p. 781b).

The phrase to know other people's lives in this context, closely allied with the activities of the malsín, persuaded me to offer, in 1961, a very negative appraisal of the squire, in contrast with Azorín's judgment of him as the most noble and worthy in Spanish history. But, more importantly, the words saber vidas ajenas , "to know other people's lives" were to become a signpost in my reading and teaching, which in the early 1950s were influenced by the irresistible imperative dimension of the writings and person of Américo Castro. And so, over the years, I collected examples of the phrase, in its exact form or in words that suggested its meaning, which inevitably led me to see the aspects of Golden Age literature I now want to evoke, basing myself on Mordecai M. Kaplan's premise that the full meaning of any text cannot be derived from the contemplation of the text itself, apart from the social, economic, psychological, and intellectual setting to which it belongs.

Antonio de Guevara, who always seems to be saying more than his words denote, even in those commonplace truths and fabulous lies that he manipulates between the remote past and his own moment, writes:

Among the inhabitants of Crete it was customary, even obligatory, not to dare ask any visitor from a foreign land who he was, what he wanted, and from where he had come, under penalty of being whipped or sent into exile. And the purpose involved in promulgating such laws was to rid men of the temptation to be curious, that is to say, to want to know other people's lives and not pay attention to their own. . . . For what men seem to devote most of their time to is asking and investigating what their neighbors are doing; what they're involved in, how they support themselves, with whom they have dealings, where they go, what places they enter and even what they're thinking; because it is not enough that they insist on asking, they even presume to guess . . . For this reason Plato said: "Know thou, if thou knowest not . . . , that the sum of all our philosophizing is to persuade and counsel men that each one should be the judge of his own life and not be concerned to scrutinize the lives of others ." (Menosprecio , 30–36)

It goes without saying—though I'll say it anyway—that despite his reference to Plato's "Know thyself" and the realm of philosophy, Guevara is really talking about what Francisco Márquez termed "el problema del rigor inquisitorial" (p. 350). Elsewhere, becoming more specific about the potential danger and destructiveness involved in knowing other people's lives, that is, saber vidas ajenas as a weapon of an Inquisition-crazed society, he observes that "I have never seen a man insult another without prying into the life he was leading, without scrutinizing his blood line, [every branch and twig of his genealogical tree] . . . or without disinterring his ancestors" (pp. 375–382). These last remarks appear in a letter addressed to a friend who had called recent converts to Christianity "dogs, Moors, Jews, and pigs." With even greater force and specificity, Guevara writes that

one solitary blemish will dishonor an entire generation. A stain on the lineage of some country bumpkin affects no one beyond him, but a stain on an hildalgo's blood affects his entire family, because it sullies the reputation of his forebears, it serves to disinter his ancestors, it leads to the investigation of his living relatives, and it corrupts the blood of those yet to be born. (Pp. 441–442)

Now, Guevara is writing these last words in answer to an Italian gentleman who had sought to implicate Fray Antonio in the disappearance of a vial of perfume. But we can hardly believe that this is the kind of offense that would destroy a family's reputation retrospectively and proleptically. Guevara's broader and deeper meaning—his condemnation of irrational intolerance—is more apparent against the background of an earlier remark to his Italian accuser: "I, sir, am determined to pay no attention to your insult, nor to respond with anger to your letter, for I take much more pride in the religious order I belong to than in the pure blood of my ancestors . . ." (p. 440).

Alonzo de Orozco, in his Victory of Death , proclaims:

O sinner, you who go lost and wandering through the sea of life! Do you want to know why every passion stirs you and draws you after it? The reason is that you forget death, because it seems to you that you are immortal . . . In the dead man's house there is the only true philosophy . . . , but in the gatherings of the living they speak of other people's lives, and not being content to speak ill of the living, they engage in a greater cruelty: they disinter the dead, with great offense to God and infamy to those who died. (P. 136 n. 7)

It is scarcely necessary to mention that the dead alluded to here are the ancestors of New Christians, or that the disinterring of the dead is an

analogue of the inquisitorial practice of exhuming and burning the mortal remains of discovered secret Jews. In 1580—as C. R. Boxer has noted—the remains of the great pioneer of tropical medicine, Garcia d'Orta, "were exhumed and solemnly burned in an auto de fe held at Goa, in accordance with the posthumous punishment inflicted on crypto-Jews who had escaped the stake in their lifetime" (p. 11). For the Judeo-Christian Mateo Alemán, those who dug for this kind of information were like hyenas "who nourish themselves on the dead bodies they disinter" (1:48). Through the animal imagery Alemán communicated what Stephen Gilman called the full horror of inquisitorial dehumanization (p. 179). Juan de Zabaleta observed that "the malicious curiosity of men is so penetrating that it perceives blemishes in the bones of those who lie buried" (p. 247). And Gracián—writing with aphoristic density—recommends that "one should not be in life a book of vital statistics, an archive of genealogies and family traditions, for to concern oneself with the infamy in other people's lives is usually an indication of one's own tainted reputation. . . ." "In such matters," he concludes, "the one who digs the deepest will be most covered with mud," for which reason one must avoid at all costs "the effort to be a walking registry of others' ignominy, which is to be, though alive, like a soulless and despised public record of the Inquisition's trials and convictions" (p. 85 no. 125). In Quevedo's Buscón , don Pablillos's mother is imprisoned by the Inquisition of Toledo "because she disinterred corpses," but not because she did it in order to know other people's lives or to destroy a reputation by discovering some trace of Jewish blood, as an inquisitor in her own right, but because, as a witch with tainted blood no less, she literally disinterred freshly buried bodies, so that "in her house were found more legs, arms, and heads than in a shrine for miracles" (p. 94). The meaning of "to know other people's lives," then, in all these contexts and any number of others that could be cited, tells us something about the inquisitorial bent of the world in which Cervantes lived while writing Don Quixote , a world in which these words from La Celestina had disastrous validity: "When you tell someone your secret, your freedom is gone" (p. 57). In Cervantes's Colloquy of the Dogs , Cipión suggests to his friend Berganza that they should take turns relating their lives, "because it will be better to spend the time in telling their own lives than in delving into the lives of others ." At another point, while discussing police officers and notaries, Cipión observes that not all notaries are corrupt, "for there are many notaries who are good, faithful, law-abiding, and eager to please without harming anybody; for not all of them extend lawsuits, or advise both parties, or pocket more than what they're entitled to; nor do they

go searching and prying into other people's lives to put them under suspicion with the law [or the Inquisition]."

In another vein, but even closer to my subject, are these words spoken yet again by Cipión, who knows something about the difficulties of finding a decent job:

The lords of the earth are very different from the Lord of Heaven. The former, before they accept a servant, first examine his lineage as if they were looking for fleas, then they scrutinize his qualifications and even wish to know what clothes he has. But to enter God's service the poorest is the richest, the humblest is the man of most exalted lineage, and so long as he sets out to serve him with purity of heart [not of blood], God orders his name to be written in his wage-book and assigns him such rich rewards that in number and excellence they surpass all his desires.

"All this, friend Cipión, is preaching," says Berganza, and of course it is. But it was a sermon that Moorish dogs (perros moros ) barked and Jewish pigs (marranos judíos ) squealed, that New Christians and even some Old Christians preached, with the hope of achieving in Spain an open society, that kind of society which—in the words of the spiritual New Christian Henri Bergson—"is deemed in principle to embrace all humanity. A dream dreamt, now and again, by chosen souls, it embodies on every occasion something of itself in creations, each of which, through a more or less far-reaching transformation of man, conquers difficulties hitherto unconquerable" (p. 251).

In Hispanic terms it was a utopian dream that a neutral society might awake from the nightmare of history, offering neutral spaces and public places where the descendants of Moors, Christians, and Jews might mingle civilly and socially, a social system in which differences in culture made no difference in society, so that different peoples could survive and flourish in and through their differences. But what was to prevail in its place was the messianic dream of the Hispano-Christians expressed in the words of Hernando de Acuña: "una grey y un pastor, solo en el suelo," "One flock and one shepherd, alone on earth."

Before looking at the positive aspects of knowing other people's lives as portrayed in Don Quixote , let me provide a few more examples of the oppressive aspects of the phenomenon. Let us hear a brief anecdote that appears in two Lope de Vega plays and in the Segunda parte de la vida de Lazarillo de Tormes by Juan de Luna.

In Lope's Mirad a quién alabáis (Look at Whom You're Praising), we read:

A Jewish swindler and cheat,

one of those that abound in the world,

had a pear tree whose fruit

he praised to one and all.

Its renown spread so far and wide

that an official of the Inquisition

sent a page of his to request

a bowl of the pears that he had grown.

The Jew became greatly alarmed

for, though it was cold weather at the time,

the slightest fear seemed to set him ablaze

[recalling, of course, the flames of the

Inquisition]. So, he put an ax to its trunk

and when at last he saw it fall,

in order to have no further cause for fear,

he sent the tree itself to the Inquisitor.

(Pp. 42b–43a)

Juan de Luna wrote:

About this point (even though it lies outside of what I am dealing with now) I will tell of something that occurred to a farmer from my region. It happened that an inquisitor sent for him, to ask for some of his pears, which he had been told were absolutely delicious. The poor country fellow didn't know what his lordship wanted of him, and it weighed so heavily on him that he fell ill until a friend of his told him what was wanted. He jumped out of bed, ran to his garden, pulled up the tree by the roots, and sent it along with the fruit, saying that he didn't want anything at his house that would make his lordship send for him again. People are so afraid of them—and not only laborers and the lower classes, but lords and grandees—that they all tremble more than leaves on trees when a soft, gentle breeze is blowing, when they hear these names: Inquisitor, Inquisition. (P. 693)

Finally, in a play of doubtful authenticity, En los indicios la culpa (Evidence Confirms Guilt), attributed to Lope de Vega, we find the following version of the anecdote:

There was once an hidalgo

who had a most fragrant

orange tree. One day it

occurred to someone to send

a messenger to him for

a sprig of orange blossom.

The one who was to deliver the message

did not find the hidalgo at home.

So, in order not to remain there,

since the dinner hour was at hand

and he was already tired of waiting,

he left word with the hidalgo 's wife

on behalf of Mr. So-and-So,

the inquisitor, that an employee of

the Holy Office had come to see him.

Scarcely had the hidalgo been

informed of the message

when he became so violently ill

that he could not even swallow a morsel of food.

He mulled over and over again in his mind

with prolix detail all that

he had ever said and done from his birth

to the present moment.

And learning finally what the messenger

had come for and that he would probably

return for more, if the whim were

to strike the inquisitor again,

the hidalgo exclaimed:

"By God, I swear that he'll have

no further reason to return to this house!"

And he sent the orange tree to him.

(P. 288a)

Let us examine the major difference in the elaboration of the three texts in order to grasp its implications for a more meaningful appreciation of each version. The central figure in Mirad a quién alabáis is a Jew. In En los indicios la culpa, the brunt of the joke is an hidalgo . In Luna's sequel to Lazarillo de Tormes, however, the victim of the Inquisitor's unintentional, unconscious threat to his very existence is a labrador, a pobre villano, "a farmer, a pitiful peasant."

We have, then, three different levels of Spanish society represented in the texts at hand: (1) a Jew, (2) a member of the lesser nobility, undoubtedly an hidalgo cansado, a convert of recent vintage, and (3) a farmer, a representative of that mythical group of quintessential Old Christians, the last vestige of pure blood on Hispanic soil. In these three figures we have the basic components, the fratricidal antagonists, of the civil war that raged on in Spain throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. By the time that Lope was writing for the theater the Jew was only a phantasmagorical presence in his land, an imaginary

threat to the catholic unity of the Spanish faith. The hidalgo, however, was a daily irritant to the average Spaniard, a stimulant for envy and resentment, an ideal scapegoat for pent-up frustrations and unfulfilled ambitions; he was the inevitable victim, the perfect object of scorn and derision, whose tainted blood was an ineradicable stigma.

Now, why would Juan de Luna change the main character of the anecdote from a Jew or an hidalgo to a peasant? It is not difficult to suggest a reasonable justification for the change. That a Jew or convert should fear the proximity of an inquisitor or the interest of some Inquisition authority in his possessions, however innocuous that interest might seem, is hardly novel or unexpected. The aesthetic delight provided by the incident derives precisely from the reinforcement of a shared truth. However, that a peasant, a farmer, should fear the mere presence of an inquisitor is an overwhelming indictment of an institution whose supposed function was to assure the religious purity and orthodoxy of an entire nation. Thus, the psychic pleasure afforded by Juan de Luna's text is of a very different order. He was a violent enemy of the Inquisition, perhaps a converso himself, and he wrote from bitterly resented exile in France. He must have found it enormously satisfying to present a peasant—not a Jew or even someone of mixed blood—as a quaking coward, for it enabled him to demonstrate with insidious subtlety that no one in Spain was beyond the reach of the arbitrary and unpredictable injustice of the Holy Office.

In the conclusion to his interlude El retablo de las maravillas (The Wonder Show), Cervantes showed the lunacy of a peasant community that assumed an army quartermaster had to be a coward simply because, as they all mistakenly believed, he was of Jewish ancestry, ex illis, "one of them" (p. 123). With vengeful genius Juan de Luna chose to make a peasant, the very symbol of Old Christianity, a coward. In the process, he revealed how all people in Spain—even lords and grandees—tremble when they hear the words inquisitor and Inquisition . Lope de Vega, faithful to the stereotypical presentation of the cowardly Jew and tainted hidalgo, made now one, now the other, the victim of a joke meant to amuse the Old Christian majority in his audience. And yet, his great gift for artistic empathy enabled him to present, even within the skeletal frame of an anecdote, the sense of anguish experienced by the hidalgo as he rehearsed in his mind a life's words and deeds—words and deeds, even a blemished birth, that might be considered heretical and could soon be the raw materials of a prolonged and painful inquisitional trial.

From three versions of a simple anecdote I have teased a series of

details that help us to experience yet again how the Inquisition—that bastion of un-Christlike Christianity—destroyed the pluralist paradise that Spain might have been.

And now let us look at the theme of knowing other people's lives in Don Quixote, surely one of those creations alluded to by Bergson, which, "through a more or less far-reaching transformation of man, conquers difficulties hitherto unconquerable." That the subject is present in Don Quixote as a kind of commonplace of the period is immediately apparent from the following references. In the opening verses of Part 1, humorously attributed to "Urganda the unknown," we find this advice:

Keep to the business at hand

and don't stick your nose into other people's

lives.

Sancho insists that he is not "one to pry into other people's lives" (p. 201) and Don Diego de Miranda, the Gentleman in the Green Coat, asserts: "I do not enjoy scandal and do not allow any in my presence. I do not pry into my neighbors' lives, nor do I spy on other men's actions" (p. 567). Finally, Doña Rodríguez informs Sancho that "squires are our enemies; for seeing that they are imps of the antechambers and watch us at every turn, such times as they are not praying—and those are many—they spend in gossiping about us, disinterring our bones and interring our good names" (p. 712).

What now remains to be done is to show the unique and genial utilization of the concept in Don Quixote, the way in which the shopworn maxim about knowing other people's lives was infused with a new and revolutionary force, to contrast with the ominously inquisitional overtones that echoed in the texts I have just been citing.

If Américo Castro impressed anything on readers of Don Quixote, it was his position that Cervantes conceived of literary creation as the re-creation of a creative process of life, of life in the making, life unemcumbered by what might be called hereditary determinism. Avalle-Arce brilliantly exemplified Castro's view in his analysis of the novel's opening paragraph, which he compared to the initial pages of Lazarillo de Tormes and Amadís de Gaula, in order to demonstrate the extraordinary freedom of the Cervantine hero. But whereas both Castro and Avalle stressed the reasons for Don Quixote's freedom and the open, undetermined nature of his future, I should like to examine what he was freed from, and how

it prepares us for the attitude toward other people's lives that will prevail throughout the work, though more prominently in Part 1.

In a sense, the first paragraph of Don Quixote is more important for what it does not tell us than for the paradigmatic, illusorily specific, yet ultimately deindividualizing details about the hidalgo's life that it does present; for the narrator has chosen to omit precisely those details that were most crucial to that scrutiny of other people's lives I have just been describing. Let us consider the novel's first two paragraphs:

In a certain village in La Mancha, which I do not wish to name, there lived not long ago a gentleman—one of those who have always a lance in the rack, an ancient shield, a lean hack and a greyhound for coursing. His habitual diet consisted of a stew, more beef than mutton, of hash most nights, bacon and eggs on Saturdays, lentils on Fridays, and a young pigeon as a Sunday treat; and on this he spent three-quarters of his income. The rest of it went on a fine cloth doublet, velvet breeches and slippers for holidays, and a homespun suit of the best in which he decked himself on weekdays. His household consisted of a housekeeper of rather more than forty, a niece not yet twenty, and a lad for the field and market, who saddled his horse and wielded the pruninghook.

Our gentleman was verging on fifty, of tough constitution, lean-bodied, thin-faced, a great early riser, and a lover of hunting. They say that his surname was Quixada or Quesada—for there is some difference of opinion amongst authors on this point. However, by very reasonable conjecture we may take it that he was called Quexana. But this does not much concern our story ; enough that we do not depart by so much as an inch from the truth in the telling of it. (P. 31)

Where was he born, what was his lineage, who are the ancestors we can investigate, inform on, scrutinize, disinter; what, even, was his family name? And we are told that these details, the indispensable material to know other people's lives, the central concern of generations of Spaniards in their literature and lives, is not of much importance to our story. And so Don Quixote is not only free in the Castronian sense to become himself, to realize his full being, but he has been freed of the fear and inhibitions provoked by that infamy that endures forever, the infamy of tainted blood that Fray Luis de León railed against in The Names of Christ, when he wrote: "A noble kingdom is one in which no vassal is considered of vile lineage, nor humiliated for his background, nor considered less well born than another. How can there be justice if some are despised and humiliated from generation to generation and the stigma is unending?" (p. 935). It is this freedom from inquisitional pressures that allows

the vision of a Spain that might have been to emerge, a Spain in which the departure of Ricote's daughter from her village is depicted in the following manner by Sancho Panza:

I can tell you that your daughter looked so beautiful when she went that everyone in the place came out to see her, and they all said she was the loveliest creature in the world. She departed weeping, and embraced all her friends and acquaintances and all who came to see her, begging everyone to commend her to Our Lord and Our Lady His Mother; and all this with such feeling that it brought tears to my eyes, and I'm not generally much of a weeper. There were many in fact who wanted to go out and capture her on the road and hide her away, but fear of breaking the king's decree prevented them. (P. 822)

Need I remind you that Ricote was a Morisco and that his daughter was leaving their village for exile? We have the feeling, though, that the Old Christian villagers loved her as much as the inhabitants of Burgos loved the Cid and feared to disobey King Alfonso's orders. Unlike the informers don Diego Coronel of the Buscón and Guzmán de Alfarache, Sancho will not betray his friend Ricote. "I will not betray you," says the authentic Christian to his Morisco friend. But he will not do treason against the King either, "to favor his enemies" (p. 821). "His enemies," says Sancho, not mine, but he does not dare to help Ricote, since he shares the villagers' fear of breaking the king's decree. And the happy ending of the episode of Ricote and his daughter is the wish-fulfilling dream of a Spain that—as Francisco Márquez has written—"instead of shedding their blood in sterile fratricidal strife, fused the blood of all Spain's children, laying aside the absurd and anti-Christian division between the pure and the tainted" (p. 335).

In this way, Don Quixote is free to face the future on his own terms, precisely because he has been freed of the unending threat involved in having a past. The specifics of his genealogy "are of little importance to our story" for the same reasons that Aldonza Lorenzo, alias Dulcinea, is lovely and virtuous, and her lineage does not matter a bit; "for no one will investigate it for the purpose of investing her with any [religious] order and, for my part"—says Don Quixote—"I think of her as the greatest princess in the world" (p. 210). For similar reasons Sancho could become a count, even if he were not an Old Christian. "I'm an Old Christian," affirms Sancho, "and that is enough ancestry for a count." This remark has been cited over and over again, when what really matters is Don Quixote's answer, in which he minimizes the significance of Sancho's Old Christian background: "And more than enough," responds Don Quixote, "but even if you were not [an Old

Christian] it would not matter, for if I am King I can easily make you noble . . ." (pp. 169–170). For Don Quixote, Sancho's Old Christian stock was as important for his becoming a count as—in Cervantes's interlude The Wonder Show —is a musician's being identified as "a very fine Christian and a well-bred hidalgo," in order to enhance his musician-ship. The ironic reply is that "such qualities are essential indeed in a first-rate musician!" (p. 117). In the dream world of Don Quixote, lineage, purity of blood, Jewish or Moorish ancestry, meant nothing. There was no Inquisition and there were no relentless investigations.

Once Cervantes has insulated his novelistic world against the real and ever-present danger of an Inquisition-style scrutiny of other people's lives, it becomes possible for the work to be comic in the Bergsonian sense: "The comic comes into being [within a neutral zone in which man simply exposes himself to man's curiosity] . . . when society and the individual, freed from the worry of self-preservation, begin to regard themselves as works of art" (p. 73).

Unamuno was right when he noted that "Don Quixote was extremely curious and given to prying into other people's lives " (p. 90), but so were almost all the other characters in the work! What matters, of course, is what was behind the curiosity. From the moment of Don Quixote's encounter with the prostitutes, transformed through his persuasive will and art into Dona[*] Tolosa and Dona[*] Molinera, we are embarked on a seemingly endless number of encounters with people who will give up the secrets of their lives—or who will create marvelous fictional existences that resemble their own—with more or less artistry to satisfy the insatiable and beneficent curiosity of their listeners. Over and over again we come to recognize the special quality of knowing other people's lives in Don Quixote, the overwhelming delight that derives from entering into the lives of others and thereby living in another dimension. A few examples must suffice.

Having heard some of the details of Grisóstomo's tragic death, recounted by a young villager named Pedro, Don Quixote interrupts to observe that "it is a very good story, and you, my good Peter, are telling it with a fine grace" (p. 93). When Pedro concludes his remarks with an invitation to attend Grisóstomo's funeral, Don Quixote responds: "I will certainly be there, and I thank you for the pleasure you have given me by telling me such a delightful story" (p. 95).

When Zoraida and the Captain arrive at the inn—one of those Hispanic inns described by Angel Sánchez Rivero as "the crossroads of life . . . , more intimate than a modern hotel because of the primitive installations, the hazards of the road, the infrequency of travel, the gen-

erous cordiality of a group of people aware of danger and sensitive to adventure, all obliged to come together in a cramped and poorly lit space to tell one another their lives" (p. 13)—people can scarcely keep from asking them to tell their life story, "but no one cared to ask just then, for at that time it was clearly better to help them get some rest than to ask them for the story of their lives" (p. 338). After they have rested, "Don Fernando asked the Captain to tell them his life's story, for from what they had gathered by his coming in Zoraida's company, it could not fail to be strange and enjoyable" (p. 345). As in so many other cases throughout the work, we are made to feel the importance of the artistry involved, the histrionics in relating a life story as a source of pleasure and edification:

Listen then, gentlemen, and you will hear a true story, and I doubt whether you will find its equal in the most detailed and careful fiction ever written.

At these words they all sat down in perfect silence; and when he saw them quiet and waiting for him to speak, he began in a smooth and pleasant voice. (P. 345)

At the conclusion of the Captain's tale, Don Fernando gives voice to the audience's reaction:

I assure you, Captain, that the way in which you have told your strange adventure has been as remarkable as the strangeness and novelty of the events themselves. It is a curious tale and full of astonishing incidents. In fact we have enjoyed listening so much that we should be glad to hear it all over again, even if it took till tomorrow morning to tell it. (P. 381)

Naturally the content of the narrated life is important; tragic events are to be lamented and joyous reunions celebrated, but what matters most is the willing suspension of belief in the Spain that really was, so as to enjoy to its fullest the parenthetical paradise of Art, offered up to us in these numerous portraits of characters as artists.

When the irresistible Dorotea completes her tale of woe, she is asked to provide some additional details:

She told him, briefly and sensibly, all that she had previously told Cardenio; and Don Ferdinand and his companions were so delighted with her story that they would have liked it to last longer, so charmingly did she tell the tale of her misfortunes. (PP. 331–332)

As if to remind us of that other world where the scrutiny of people's lives is a sinister and venomous pursuit, there are chapters like the "Scrutiny of Don Quixote's Library," a small-scale model of an Inquisi-

tion trial, rich in the lexicon of such investigations, which ends with the heartless destruction of innocent victims. The text reads:

Some [books] that were burnt deserved to be treasured up among the eternal archives, but fate and the laziness of the inquisitor forbade it. And so in them was fulfilled the saying that the saint sometimes pays for the sinner. (P. 64)

Unamuno, blind to the possible meanings of this chapter, refused to examine it, because "it deals with books and not with life" (p. 46). But however much the discussion of the books is conducted in aesthetic terms, ultimately we are forced to believe that these books, constantly described in human terms, are the Anne Franks of Cervantes's day, the innocent victims of whose beauty and genius we have been deprived through the indifference, the cruelty, if not the "laziness of the inquisitor": "The priest was too tired to look at any more books, and therefore proposed that the rest should be burned without further inspection" (p. 63). It is indeed ironic that an escrutinio, a scrutiny, an inquisition, should end on such a note, when Covarrubias tells us that escudriñar means "to look for something with excessive meticulousness, care and curiosity"; escudriñador "he who is curious to know secret things." He concludes, cryptically, that "there are men who are tempted to find out what others have locked up in their breasts and at times what God has concealed in his own" (p. 543a).

In direct contrast with the Inquisition-like proceedings of the scrutiny made in Don Quixote's library is the knight's encounter with the galley slaves and his insistence—due to the infinite care and humanity in his notion of justice—that each galley slave be discreetly and sympathetically examined, since it is "better for ninety-nine guilty to escape than for one innocent person to be wrongfully condemned." Ginés de Pasamonte, a galley slave who knows the dangers that lurk behind the scrutiny of other people's lives—Lope de Vega's "new mode of scrutiny"—and has learned to be wary of such interrogations, tells Don Quixote "you annoy me with all your prying into other people's lives " (p. 176). And these words, which—in the interpretation of Ginés and the intention of Don Quixote—exemplify the collusion of the real world with a utopian Spain, suggest yet another dimension to Don Quixote, one more way to enjoy and appreciate the genius of Cervantes.

In 1973 the Nobel Prize-winning German novelist Heinrich Böll was asked: "How do you think a novel about Germany in the 1930s would differ from the idea that most people have of it?" His reply was:

It would be at the same time both worse and better than the propaganda was. If you imagine that children would really give the names of their parents to the police for political offenses, it is terrible. There's really a Shakespearean tragedy behind such a small fact. Reading it as a note in the press, you wouldn't get that. It would be a terrible fact, but you would forget about it. Yet out of that fact a writer can make a very informative and true novel, one that is much more important than nonfiction. What is behind it is up to me, my imagination and my experience of the time.

And, paradoxically, literature makes it possible for us to enjoy, to derive pleasure as well as information and edification from reading and experiencing in an imaginatively insulated setting—the protective privacy of a book, the communal comfort of a theater, the womb-like intimacy of a darkened movie house—the suffering and persecution of others as well as their joys and satisfactions.

Having mentioned suffering and persecution, I should like to close with some general observations, particularly since a distinguished Hispanist claimed some years ago that "as many as ninety-nine out of every hundred conversos lived unmolested by the Inquisition," as if in some paradisiacal sanctuary. (Can one live "unmolested"—even psychically unmolested—with the potential threat of persecution always at hand?) Sister Marie Despina recently wrote in a moving essay entitled "The Accusations of Ritual Crime in Spain" that one is amazed by the similarities between the procedures of the Spanish Inquisition and those of the Russian Gulag, the similar treatment of the accused, overwhelmed by terror, torture, and utter despair (pp. 61–62). In a statement characteristic of any number of references to the oppressively negative effects of the Inquisition on Hispanic life, the great Argentine statesman and author Domingo F. Sarmiento declared that

the crime of the Inquisition is to have destroyed in daily practice and in one's intimate feelings the notion of human rights, the sense of security of life before the law, the awareness of justice, the limits of public power . . . Since crimes of the mind cannot be determined by a law or code, the Spaniard and the Hispanic American lived [because of the Inquisition] under the fear of possibly committing a crime by thinking. (P. 184)

In her book on The Conversos of Majorca, Angela Selke reminds us that

in stressing the terrible injustice which the Holy Office committed by persecuting and punishing innocent people, there is an implicit justification of such persecutions provided they are based on true accusations and verified

evidence. Yet such an attitude tends to obscure what today [we recognize and accept]—that is, the fundamental injustice of all persecutions for dissident beliefs, be the charges true or false. . . . [We] must reject as contrary to Christian ethics not only the abuses of the Inquisition or its proceedings, but, above all, the radical injustice inherent in any institution whose business—whatever its professed purpose may have been—[is] the systematic organization of such persecutions. (P. 19)

Like many New Christians, Cervantes dreamed of a Spain that might have been, recognizing that its fulfillment was impossible. The visionary religious syncretism that the Moriscos of Granada strove to achieve, certain that every individual could be saved under the law of Christ, under that of the Jew, and that of the Moor, if he kept the precepts of his religion faithfully; the unified kingdom of heaven on earth which the New Christians struggled vainly to establish in Spain; the mythical Golden Age of ideal justice which Don Quixote imagined he could restore, can best be summed up in these words of Wallace Stevens:

He had to choose. But it was not a choice

Between excluding things. It was not a choice

Between, but of. He chose to include the things

That in each other are included, the whole,

The complicate, the amassing harmony.

(P. 124)

The majority of Spaniards in the retrospectively halcyon years of Spain's artistic Golden Age chose, through the Inquisition, to renounce the opportunities for "amassing harmony," and to this day Spain has endured the consequences of that tragic choice.

* This essay is for Robert Silverman, who taught me to appreciate the beauty and power of words.

Unforeseen circumstances have made it impossible for me to provide the footnotes I had planned to include. Unless otherwise indicated in the list of works cited, the translations are my own.

Works Cited

Alemán, Mateo. Guzmán de Alfarache, edited by Samuel Gili y Gaya. 5 vols. Clásicos castellanos, vols. 73, 83, 90, 93, 114. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1942-1950.

Anonymous. The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes, translated by Harriet de Onís. Great Neck, N.Y.: Barron's Educational Series, 1959.

Avalle-Arce, Juan Bautista. "Tres comienzos de novela." In Nuevos deslindes cervantions. Barcelona: Ariel, 1975.

Bergson, Henri. "Laughter." In Comedy, edited by Wylie Sypher. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1956.

Boxer, C. R. Two Pioneers of Tropical Medicine: Garcia d'Orta and Nicolás Monardes. Diamante, vol. 14. London: The Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Councils, 1963.

Cervantes, Miguel de. The Adventures of Don Quixote, translated by J. M. Cohen. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1950. Translation slightly revised.

———. The Colloquy of the Dogs. In Six Exemplary Novels, translated by Harriet de Onís, 3:12-13. Great Neck, N.Y.: Barron's Educational Series, 1961. Translations slightly revised.

———. ———. In The Deceitful Marriage and Other Exemplary Novels, translated by Walter Starkie, 249, 258, 276. New York: New American Library, 1963. Translations slightly revised.

———. ———. In Exemplary Stories, translated by C. A. Jones, 197, 204-205, 220. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1972. Translations slightly revised.

———. El retablo de las maravillas. In Interludes, translated by Edwin Honig. New York: New American Library, 1964. Translation slightly revised.

Covarrubias, Sebastián de. Tesoro de la lengua castellana o española, edited by Martín de Riquer. Barcelona: Horta, 1943.

Despina, Sor Marie. "Las acusaciones de crimen ritual en España." El olivo (Madrid) 3, no. 9 (1979): 48-70.

Gilman, Stephen. "The Sequel to El villano del Danubio. " Revista Hispánica Moderna 31 (1965): 175-185.

Gracián, Baltasar. Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia, edited by Arturo del Hoyo. Madrid: Castilla, 1948.

Guevara, Fray Antonio de. Menosprecio de corte y alabanza de aldea, edited by M. Martínez de Burgos. Clásicos castellanos, vol. 29. Madrid: Ediciones de "La Lectura," 1928.

———. Libro primero de las Epístolas familiares, edited by José María de Cossío. Vol. 2. Madrid: Aldus, 1952.

León, Fray Luis de. De los nombres de Cristo, edited by Federico de Onís. Vol. 2. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1917. Material adapted and reduced.

Luna, Juan de. Segunda parte de la vida de Lazarillo de Tormes. In La Celestina y Lazarillos, edited by Martín de Riquer. Barcelona: Vergara, 1959.

Márquez Villanueva, Francisco. Personajes y temas del Quijote. Madrid: Taurus, 1975.

———. "Crítica guevariana." Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica, 28 (1979): 334-352.

Orozco, Alonso de. Victoria de la muerte. Cited in Américo Castro, An Idea of History, edited by Stephen Gilman and Edmund L. King. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1977. The translation by Carroll Johnson is slightly revised.

Quevedo, Francisco de. El buscón, edited by Américo Castro. Clásicos castellanos, vol. 5. Madrid: Ediciones de "La Lectura," 1927.

Rojas, Fernando de. The Spanish Bawd: La Celestina, translated by J. M. Cohen. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964.

Sánchez Rivero, Angel. "Las ventas del Quijote." Revista de Occidente, año 5, vol. 17, no. 46 (1927): 1-22.

Sarmiento, Domingo F. Conflicto y armonías de las razas en América. Buenos Aires: "La Cultura Argentina," 1915. Cited by Daniel E. Zalazar, "Las ideas de D. F. Sarmiento sobre la influencia de la religión en la democracia americana." Discurso Literario, 2 (1985): 541-548.

Selke, Angela S. The Conversos of Majorca: Life and Death in a Crypto-Jewish Community in XVII Century Spain, translated by Henry J. Maxwell. Hispania Judaica, vol. 5. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, Hebrew University, 1986.

Stevens, Wallace. "Notes toward a Supreme Fiction." In Selected Poems. London: Faber and Faber, 1960.

Unamuno, Miguel de. Vida de Don Quijote y Sancho. Colección Austral, vol. 33. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1949.

Vega, Lope de. En los indicios la culpa. In Obras de Lope de Vega, publicadas por la Real Academia Española (nueva edición), vol. 5. Madrid: Tipografía de la "Revista de Archeologia, Bibliografia y Museos," 1918.

———. Mirad a quié alabáis. In Obras de Lope de Vega, publicadas por la Real Academia Española (nueva edición), vol. 13. Madrid: Imprenta de Galo Saez, 1930.

———. El niño inocente de La Guardia, edited by Anthony J. Farrell. London: Tamesis Books, 1985.

Zabaleta, Juan de. El día de fiesta por la mañana, edited by María Antonia Sanz Cuadrado. Madrid: Castilla, 1948.