Preface

As with most books, the genesis of this one is a complex mixture of lifelong interests, connections, and contingencies. But this book is more personal than most. I was born and spent a significant part of my youth in Oxford, Mississippi, where I had the pleasure of occasional encounters with William Faulkner, a distant relative on my father's side. Both families had come originally from Ripley, Mississippi, some fifty miles to the northeast in the neighboring county of Tippah. I include as an appendix a recent letter to my son, in which I recall my acquaintanceship with Faulkner and the long connections of our family with his. Some readers may prefer to read this letter first.

From my father and his family, I imbibed a passion for history, particularly of the South and of what Faulkner called our own little postage stamp of native soil in north Mississippi. As an undergraduate history major at the University of Mississippi, this interest was confirmed to the point that I decided that I wanted to read, write, and teach history as my life's work and to pursue a Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. There, while majoring in American social, cultural, and intellectual history, I minored in art history, specializing in the history of architecture. The latter pursuit helped confirm another childhood passion, largely engendered by my mother, for the built environment and what would come to be called "material culture."

Though she gained local renown as a first-grade schoolteacher, my mother was secretly an architect manqué, gently trespassing, with me in tow, building sites throughout our region whenever they came to her attention. I remember still her thoughtful critiques of the works in progress. For her time and place, she had a sophisticated sense of space and design, which she enthusiastically communicated to me. She was also a knowledgeable collector and arranger of furniture and objects, and I

recall the frequent screeching of automobile tires as we would stop suddenly to cruise antique and thrift shops. I was cautioned not to touch, but of course I always did. Stimulated by my penchant for architecture and its accoutrements, I also developed an early interest in photography and began, as a teenager, what would become a lifelong pursuit of documenting the built environment, particularly that of north Mississippi. Over three-fourths of the photographs in this book are mine.

At Wisconsin and later at UCLA, where I began teaching in 1968, my early devotion to southern history and literature waned in deference to my growing commitment to the social and cultural history of architecture. My first book, Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner (1974), focused on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century issues involving the rise of the skyscraper and the birth of modern American city planning. In Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture (1982), I analyzed the development of early and middle twentieth-century modernism in Europe and America. Its publication coincided with a Neutra exhibition I cocurated with Arthur Drexler at New York's Museum of Modern Art, a show that traveled for two years to venues on both sides of the Atlantic.

Then, in the mid-1980s, as a respite from these endeavors, I decided to take what I thought would be a break from architecture, to clear my head by immersing myself in something different. For that "something," I chose a serious but relaxed reexamination of Faulkner, rereading in ripe middle age the novels and stories I had devoured in my twenties, though certainly then with less than total comprehension. Now, with an additional quarter century of reading, writing, and living behind me, I began, without other conscious agenda, to reexperience the achievement of America's greatest writer. But, as a good Calvinist boy, as a diligent son of the Protestant work ethic, I soon realized that I could never take on so vast a project just for fun, and to assuage my guilt for such happy self-indulgence I began—furtively at first, then more consciously and aggressively—to underline the architectural passages and references.

Then my compulsive academic superego took over and reminded me of the possibility—indeed the imperative—of doing a "nice little article" on Faulkner's architecture. This momentum was adventitiously encouraged by an invitation from the University of Mississippi Center for the Study of Southern Culture to attend the annual August "Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha" conference and to lead an architecture tour of the town and the county. I was also asked to give a short talk on the subject, which led in 1988 to an article in PLACES: A Quarterly Journal of Environmental Design . That, I assumed, was the end of an enriching diversion, and I returned to an earlier commitment to write a series of essays, and ultimately a book, on modernist architectural

culture in Southern California. Yet again, my trajectory was happily interrupted by another invitation from the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, this time to develop a larger paper on the architecture of Yoknapatawpha for the 1993 conference on "Faulkner and the Artist." This inspired another round of rereading and rethinking, with encouragement from various fronts—including, most importantly, the University of California Press—to expand my paper into a book.

In all successive versions of this project, from the beginning paper to its present incarnation, I have taken as a model the approach of the critic Malcolm Cowley in his epochal anthology The Portable Faulkner , first published by Viking in 1946, when most of the author's work was no longer in print. What Cowley did, with Faulkner's consent, was to take apart the oeuvre and put selected pieces of it together again in the form of a compressed, though still sprawling, chronological saga. That is, of course, a method and an attitude that is logical and congenial to me and most historians. Like Cowley, I have disassembled and reassembled Faulkner's work in a roughly chronological way, though here with an emphasis on architecture and the built environment. Though I illustrate my ideas with specific examples, this essay does not purport to be an encyclopedic history of north Mississippi architecture. Neither does it attempt to cover every reference to architecture in Faulkner's novels and stories or to evaluate the role of architecture in each particular work. To avoid redundancy in this short book, many vivid images were reluctantly passed over. This is a study of how the built environment served Faulkner as background and foreground, as symbol and subject, in the long, grand, diachronic sweep of the Yoknapatawpha narrative. In this pursuit, I have quarried not only major works, such as Absalom, Absalom !, but such lesser achievements as Mosquitoes and Knight's Gambit , to document the pervasiveness of architecture in Faulkner's thinking as a whole. This book explores Faulkner's use of architecture and its accoutrements, not only as another way of understanding Faulkner's work, but as a way of appreciating the power of architecture to shape and reflect what Faulkner, himself, called the comedy and tragedy of being alive .[1]

Plate 1

John McCready, "Oxford on the Hill" (1939). City Hall, Oxford, Mississippi.

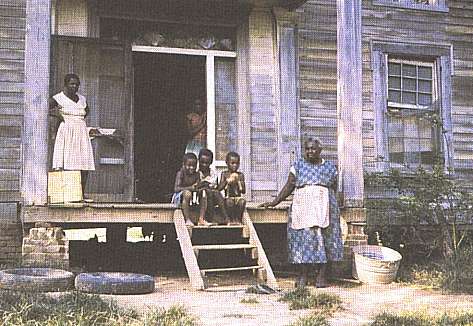

Plate 2

Dogtrot House, Lafayette County, Mississippi (late nineteenth century, demolished).

Plate 3

Dogtrot House, Lafayette County, Mississippi (hate nineteenth century, demolished).

Plate 4

Jones House, Lafayette County, Mississippi (mid-1850s, demolished).

Plate 5

Shipp House, Lafayette County, Mississippi (ca 1857, demolished).

Plate 6

Neilson-Culley House, Oxford, Mississippi,

attributed to William Turner, architect (1859).

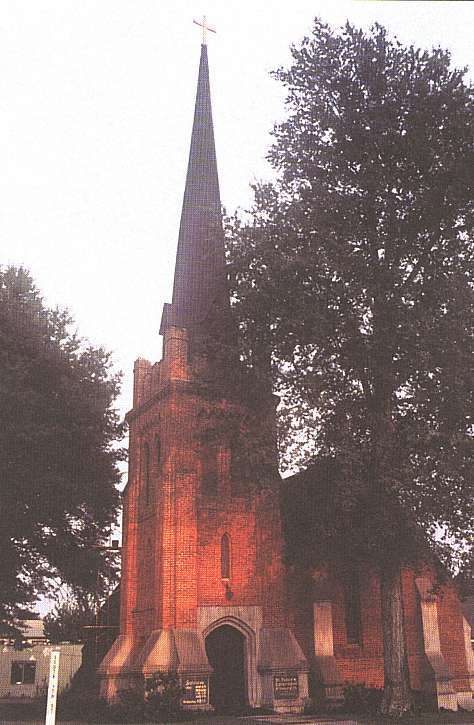

Plate 7

St. Peter's Episcopal Church, Oxford, Mississippi,

attributed to Richard Upjohn, architect (1859).

Plate 8

Airliewood, Holly Springs, Mississippi (ca 1858)

Plate 9

Pegues House, Oxford, Mississippi, Calvert Vaux, architect (1859).

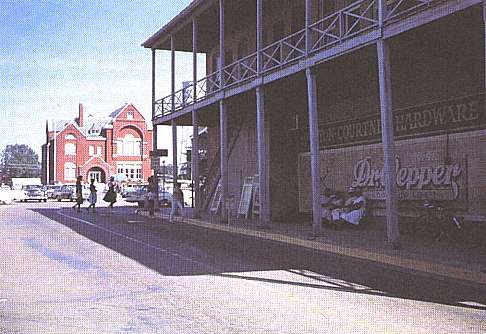

Plate 10

Old Federal Building (1885) and double-porched structures

leading to Courthouse Square, Oxford, Mississippi.